Credit: Monaco Press Centre Photos

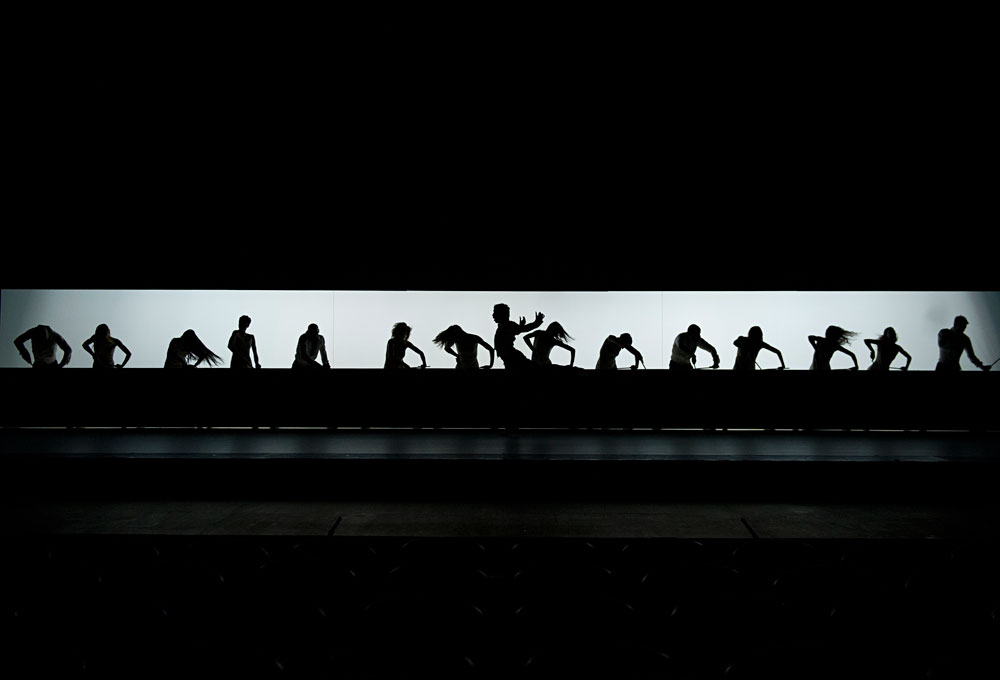

The Summer Dance season of Ballets de Monte-Carlo opened last week with Jean-Christophe Maillot’s Vers un pays sage and Sheherazade, and continues this week with a triple bill of three very different works – Alexander Ekman’s Rondo, Blind Willow by Ina Christel Johannessen and a new work by Jeroen Verbruggen, Arithmophobia.

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

Rhythm is the theme that runs through Ekman’s joyful ballet, Rondo. Described as “a love letter to the beats of our body movements”, it includes both tap dancing and ballet, delving into an exploration of man’s primal urge to dance. It’s rhythm, not music, that invites us to dance, says Ekman, so from the moment the curtain rises, each of the five dancers uses their body to perform an individual rhythmic segment which, when they’re strung together, creates a chain of sound which develops into a combination of steps and movements.

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

In the succession of sequences which follows, the dancers, through their imagination and skill, contrive to outdo each other in their individual representations of rhythm. The ballet has a festive air about it, with the transformation of the Company into “a giant mechanical piano” – a concept which is consistent with the humour and creativity for which this choreographer is known. “It has been a great joy creating this piece together with the dancers,” he says. “Never thought I would ask someone to literally run on a piano or bang its keys with their feet.”

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

Ina Christel Johannessen has taken the title of her ballet, Blind Willow, from a book of short stories – Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman – by award-winning Japanese writer, Haruki Murakami. “The blind willow,” she says, “looks small on the outside, but it’s got incredibly deep roots, and actually, after a certain point it, stops growing up and pushes further and further down into the ground. As if the darkness nourishes it”. For her imagery, though, Johannessen has turned to the Greek mythological figure, Themis – the personification of divine or natural law, order and justice – who was depicted with a bandage over her eyes, representing the objectivity with which justice should be meted out – and holding a pair of scales in one hand and a sword in the other.

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

“The dancer in the ballet who chooses to blindfold herself is perhaps in denial of wanting to see or to be,” says Johannessen, “filtering out her surroundings, because of the difficulty, otherwise, in remaining objective. The scales represent the dancers’ investigation and challenge of balance in the body – the detail in the touch of a hand, a word, a gaze – how may that pull us off balance or back on balance, THAT is important for me”.

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

Arithmophobia, the title of Jeroen Verbruggen’s ballet, is the suffering associated with the fear of numbers, and although he translates this fear into a reflection on the remaining time in which we have to live, he does it in such a way as to avoid the gloom and doom which might be associated with that subject. Each of the eight dancers on stage portrays a personal story, none of which is dark. Verbruggen, a member of the Company, has drawn inspiration from a range of written works – the Apocalypse of Saint John in particular – pulling them together to create a performance which is said to be full of surprises.

Credit: Ballets de Monte-Carlo

He explains that despite the serious nature of the subject matter, Arithmophobia is actually an allusion to the ‘Acte blanc’ in romantic ballet – the often carefree act in which everything is light. “The end of the world,” he says, “will mean everyone dying together at the same time. A more comforting thought than travelling through life alone.” The work is set to Mahler’s 10th “unfinished” symphony, adapted for the occasion by electronic artist Matthew Herbert.

Ballets de Monte-Carlo’s triple bill takes place in the Salle Garnier, Opéra de Monte-Carlo, from 17th to 19th July. The Opéra de Monte-Carlo, is part of the Monte-Carlo Casino, designed by Charles Garnier and opened in 1879.